Thinking ChatGPT

Published:

The emergence of ChatGPT ignited my big AI dream again. Many friends around me considered it all-powerful and were worried that they might be replaced by AI one day. Now I’d like to explore this language model, making it less mysterious to myself.

BERT

In 2018, the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) entered the era of Large Language Models (LLMs). Google’s BERT model emerged and surpassed all previous models, achieving the best performance in various NLP tasks. Here is an example to illstruate BERT’s function:

Please fill in the blank: “_______, along with Alibaba and Tencent, became the three giants of China’s internet industry.” What should go in the blank? Some people may answer “Baidu,” while others may think “ByteDance” is also correct. But it can’t be any other word. Regardless of the answer, it indicates that the word in the blank is determined and influenced by the context.

BERT’s main task is to randomly mask out some words from a large-scale corpus, creating a fill-in-the-blank format like the example above, and continuously learn what should be filled in the blanks. The training and learning of language models involve understanding complex contextual relationships from vast amounts of data.

GPT-1

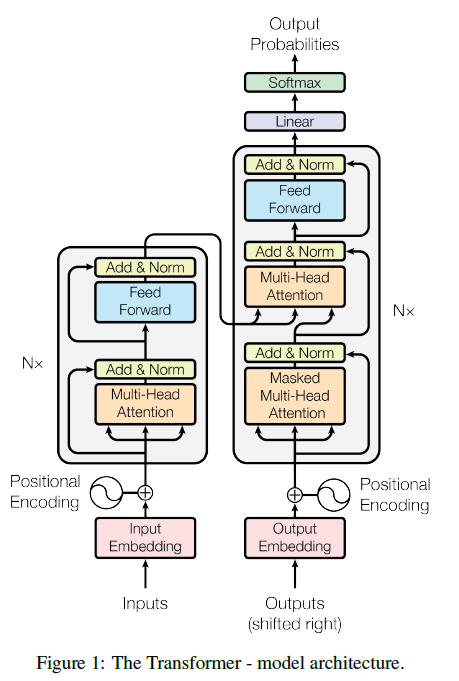

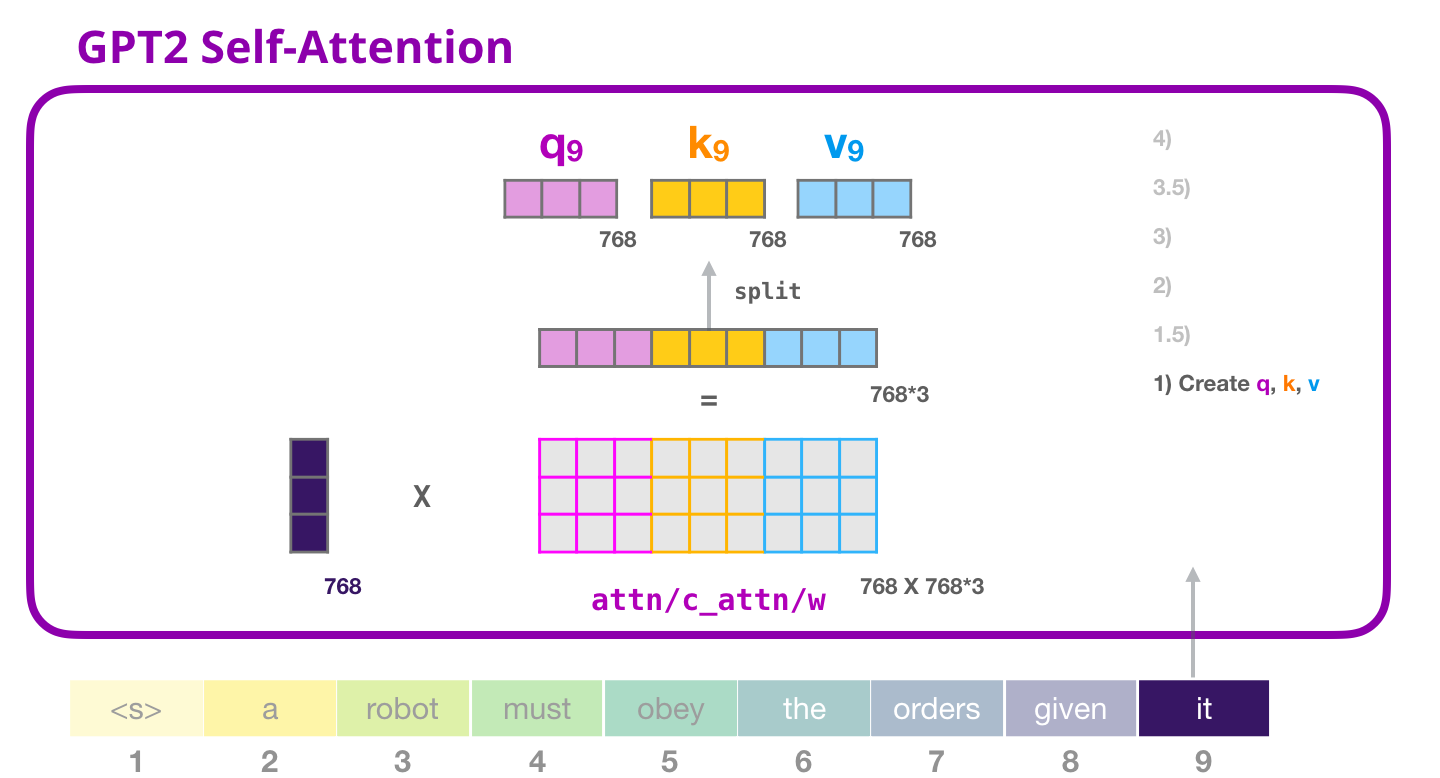

Meanwhile, OpenAI introduced an initial GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) model before BERT. The basic idea behind both models is the same: utilizing the Transformer, an encoder-decoder architecture, to capture the interconnections within the text. The concept of encoding and decoding is widely used in various fields. In the field of NLP, language processing generally involves three steps: Receiving spoken or written language -> Understanding in the brain -> Outputting the desired language.

Language is an explicit entity, but how the brain comprehends, transforms, and stores language remains a mystery (waiting for biologists’ achievements!). Thus, the process of the brain comprehending language involves encoding it into a form that is understandable and storable, which is known as language encoding. Conversely, expressing thoughts in the brain using language is called language decoding. In language models, both the encoder and decoder are composed of Transformer components.

Transformer encoder-decoder model

Without delving into the internal structure of the Transformer (I would do that later), let’s focus on the differences between BERT and GPT. The main difference lies in the fact that BERT only utilizes the encoder for model training, while GPT only uses the decoder. They have taken different paths. From my understanding, GPT’s decoder model is more suitable for text generation tasks.

In my opinion, GPT-1 is slightly inferior to BERT, coupled with its relatively lesser publicity, resulting in less impact. In essence, LLM is an extremely complex encoder that represents text as a vector, which aids in solving NLP tasks.

GPT-2

After BERT gained popularity, many models emerged following the trend, such as Albert, RoBERTa, ERNIE, BART, and many more. Initially, a simple fill-in-the-blank task significantly improved language models. Consequently, researchers began exploring other language tasks to enhance model training. Creating language tasks is relatively straightforward. Tasks like sentence shuffling and reordering, multiple-choice questions, true or false questions, error correction, and word prediction can be devised and added to the pre-training data.

If creating tasks is possible, adding various NLP task datasets to the pre-training phase is also feasible. Machine translation, text summarization, domain-specific question-answering tasks, and more can all be incorporated. This process is similar to the human brain. The brain is highly stable and adaptable, capable of reading poetry, learning mathematics, acquiring foreign languages, reading news, and listening to music. In short, it is versatile. Traditional NLP models, on the other hand, are limited in their functionality. Text classification models can only classify, tokenization models can only tokenize, and machine translation models can only perform translation. They lack flexibility.

GPT-2 learning progress

GPT-2 builds upon GPT-1 by incorporating multiple tasks, expanding the dataset and model parameters. By training multiple tasks within the same model, another issue arises. The model’s capacity goes beyond the tasks themselves. For example, the statement “John’s mother is Mary” contains information that is relevant across different tasks. It can be used for translation, classification, error detection, and more. In other words, the information is detached from specific NLP tasks and can be applied successfully across various tasks. This is known as meta-learning. Essentially, it means the language model is versatile.

GPT-3

A large model within large models (a super large model).

First and foremost, the size of the dataset used in GPT-3 is enormous, reaching trillions, and the model parameters are also massive, in the magnitude of billions. The learning process is highly complex, and the computations are extensive. The computational complexity of GPT-3 exceeds that of BERT-based by several orders of magnitude. All of this requires significant financial investment. Indeed, all you need is money. These colossal models allow GPT-3 to excel in challenging NLP tasks such as generating human-indistinguishable articles and even writing SQL queries, React, or JavaScript code.

As mentioned earlier, GPT models are trained solely on the decoder part, making them more suitable for text generation. In essence, the model is a black box—input a sentence, output another sentence. This is known as the dialogue mode. How do we learn our native language? We start from infancy, listening and speaking—engaging in dialogue. And how do we learn a foreign language? We study textbooks, listen to broadcasts, memorize vocabulary. But we lack dialogue! This lack of efficient language learning through dialogue explains why our proficiency in foreign languages is often challenging to improve.

The same principle applies to language models. Dialogue is the ultimate task that encompasses all NLP tasks. With dialogue, there is no need for modeling the decoding process as in traditional NLP, such as sequence labeling, which requires the use of decoding algorithms like CRF. In the world of dialogue, these are all redundant. CRF is a classic technique, and in the realm of deep learning, it has only been a few years since CRF was surpassed. The rapid development of artificial intelligence is truly remarkable. (Sigh…)

In-context learning Traditional pre-training consists of two stages: training the model on a large dataset and fine-tuning it using labeled downstream task datasets. This has been the basic workflow for most NLP models.

GPT-3 disrupts this conventional approach. It introduces in-context learning, here is an example. User input to GPT-3: “你觉得Alexander Suen是个好人吗?”

- GPT-3 output 1: “I think he’s nice.”

- GPT-3 output 2: “Who is Alexander Suen?”

- GPT-3 output 3: “Are you hungry? Let me make you a bowl of noodles…”

- GPT-3 output 4: “Do you think Alexander Suen is a nice guy?”

Ideally, for a machine translation task, we would prefer the last response, while for a dialogue task, we would want either of the first two responses. The sentence about making noodles is unrelated and of low quality as a dialogue response.

This is where in-context learning comes in. We guide the model by teaching it what it should output. If we want it to provide a translation, we give it the following input: User input to GPT-3: “Please translate the following Chinese sentence into English: ‘你觉得Alexander Suen是个好人吗?’”

If we want the model to answer a question, User input to GPT-3: “What do you think, is Alexander Suen a good person?”

In this way, the model can give targeted responses based on the user’s prompts. We don’t simply instruct the model; it’s better to provide demonstrations, which aligns with our usual approach. When a teacher assigns an essay, our initial reaction is to refer to sample essays for inspiration.

By adding demonstrations to the example above, we get the following input:

User input to GPT-3: “Please translate the following Chinese sentence into English: ‘苹果’ => apple; ‘你觉得Alexander Suen是个好人吗?’ =>”

The translation of “苹果” to “apple” serves as a demonstration, indicating what the model should output. A prompt with one example is called zero-shot, and multiple examples are known as few-shot.

Adding several examples is sufficient. We can’t provide too many instances, after all: First, we don’t have an abundance of labeled data, and second, providing too many examples would make it similar to the fine-tuning process.

During GPT-3’s pre-training, multiple tasks are learned simultaneously. For example, mathematical calculations (maybe not so powerful yet), error correction, and translation are performed together. This resembles the concept of prompts, which gained popularity recently.

This guided learning approach has shown astonishing results on large-scale models: by providing one or a few demonstration examples, the model can generate correct answers. It’s worth noting that this is only achievable with large-scale models. Models with several billion or tens of billions of parameters won’t suffice. (We don’t have small models here; we have large models, extremely large models, and gigantic models. Even our brains contain 86 billion neurons afterall)

ChatGPT

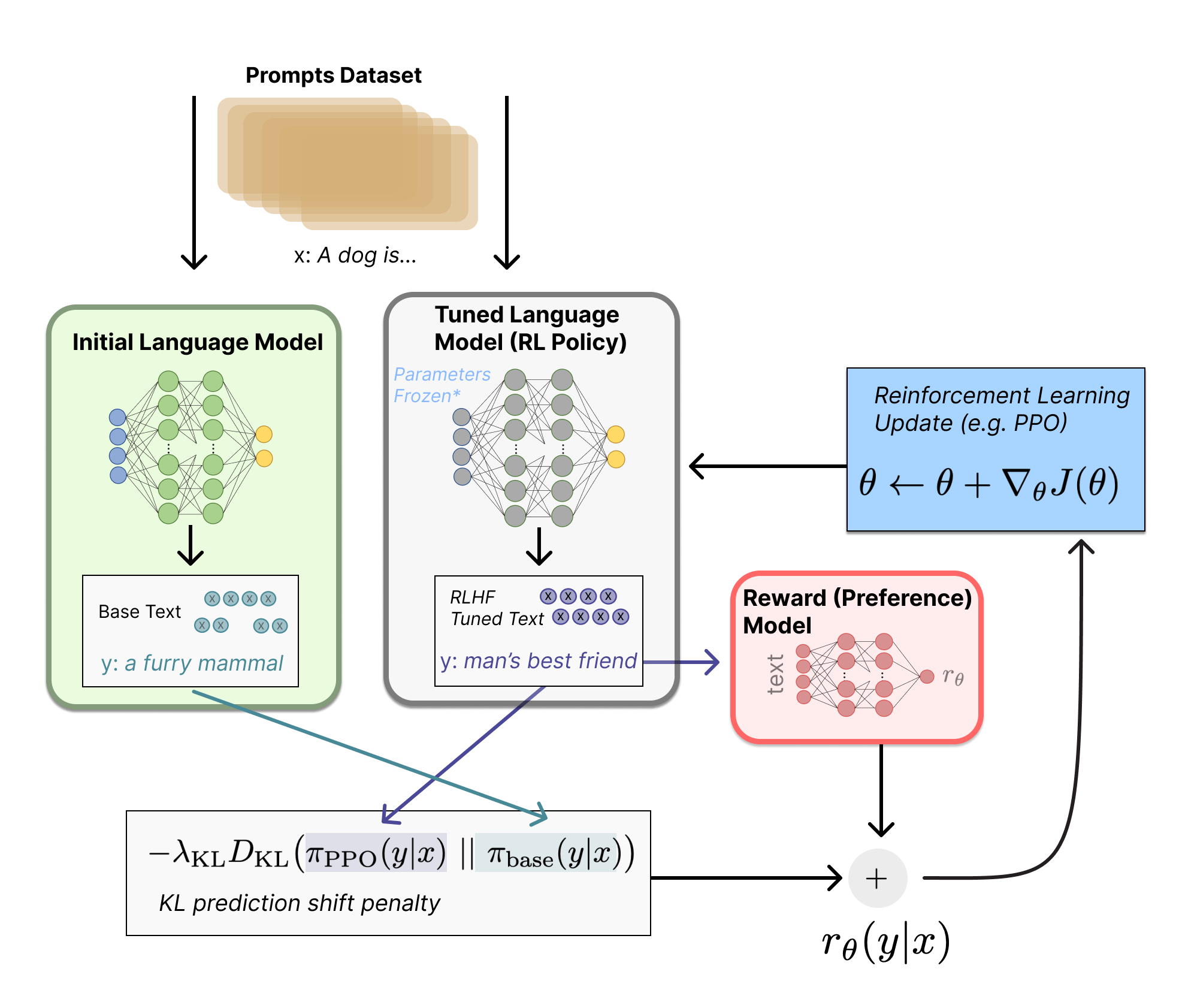

The ChatGPT model is similar to GPT-3 with minimal differences. The main change lies in the training strategy, which now incorporates reinforcement learning.

Several years ago, AlphaGo defeated the Go world champion, Ke Jie (I was only a middle school student then). This accomplishment demonstrated that given suitable conditions, reinforcement learning can surpass human capabilities and approach a state of near-perfect mastery. Reinforcement learning is akin to biological evolution. In a given environment, the model adjusts its strategy based on rewards and punishments derived from the environment. (This is why I am interested in biological evolution and biology-inspired AI:)

Reinforcement learning is highly applicable to games such as Go and other board games because the environment for AlphaGo, for instance, is the game board—it encompasses the entire world for the model (while in reality, the entire world is hard to totally include). The model continuously adjusts its strategy based on the state of the game board and the outcome (win or lose) to defeat human players like Ke Jie.

A few years ago, someone asked, “Can we apply reinforcement learning to NLP? How can we do it?”

The initial response was mostly pessimistic. The reason is that NLP relies on the entire real world—the universe of all things describable by language—for its environment. Therefore, evaluating the quality of model outputs requires rewards and punishments, which are challenging to design. Unless humans provide manual feedback step by step.

However, OpenAI’s ChatGPT has managed to address this challenge.

If we need manual feedback and rewards, why not hire 40 workers to annotate the data? This type of human-operated reward is known as Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

RLHF

The specific process employs reinforcement learning to train the model. Traditional language modeling methods have been abandoned. The key lies in the second step—constructing a reward function. In AlphaGo, the reward function determines the winner after a game of Go, and a single program function is sufficient. In ChatGPT, 40 human workers continuously sift through the model’s output to judge which sentences are good and which are of low quality. This process trains a reward model. The reward model evaluates the quality of the model’s output based on the rewards.

As long as the pre-training model is connected to the reward model through an interface, the pre-training model will begin to perceive rewards in a similar way to perceiving the real world. I coined the term “Reward Matrix Model” myself because the reward model here perfectly aligns with the world constructed in the movie “The Matrix”. Rather than saying that ChatGPT is fitting the real world, it is more accurate to say that it is accountable to the reward matrix. The reward matrix is also manually annotated, and it does not directly fit the real world. It only makes binary judgments on whether the model aligns with the real world. The alignment of the reward matrix with the real world determines the quality of ChatGPT that we perceive. Now we no longer need to directly fit text pairs for machine translation or fit data pairs for news classification. Instead, we only need to fit the reward matrix. By doing so, we can obtain this powerful model.

However, technological advancements are not limited to the present stage. Are there alternative approaches that can effectively represent the intricacies of the real world? Is it feasible to emulate biological intelligence in machines? The anticipation of witnessing a promising future fills me with great excitement.